|

Topic of the hearing was Section 404 of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1972 (FWPCA) which designates the Secretary of the Army, acting through the Army Corps of Engineers, to permit discharge of dredge and fill material into the United States waters, including wetlands. The 1977 Clean Water Act amendments to FWPCA establish certain permit processing time limits, provide for general permits, provide for state administration of wetland programs with federal approval, and call for agreements between the Corps and other federal agencies.

Corps Permit System Challenged

As Murkowski pointed out in his opening remarks, it has been some five years since Congress took any action on the wetlands permit process. Considering the fact that there are 223 million acres of wetlands in Alaska (57 percent of the state, 75 percent of the North Slope, and 70 percent of Southeast are in wetlands), he felt that reconsideration of the wetlands issues was appropriate.

But the real reason for the wetlands hearings was that considerable pressure had been put upon Congress by both industry, private citizens, and the Administration to radically alter the provisions of the Clean Water Act, particularly the Corps permitting system. The issues is before Congress this session. Senate Bill 777 sponsored by Senator Bentsen of the Committee on Environment and Public Works would restrict the provisions of Sec. 404 to “waters which are used or are susceptible to use in their natural condition or by reasonable improvement, as a means to transport interstate or foreign commerce shore ward to their ordinary high water mark…” This change would substantially restructure the administration of Sec. 404 in Alaska, excluding many important Alaskan wetland resources from federal oversight under the 404 program.

|

In June 1982, the Government Accounting Office — the budget watchdog for Congress — issued a report calling for “More Effective Wetlands Permits” to facilitate Alaskan oil and gas exploration and development. The paper stated:

Delayed issuance of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers wetlands permits hampers Alaskan oil and gas projects. Automatic extensions to the public comment period and late issuance of public notices contribute significantly to this delay. In addition, the Corps imposes permit stipulations without requiring documentation and support from the agencies which propose them. The necessity for some of these stipulations is questionable…

The Corps and the Alaska Wetlands Task Force have tried to expedite permit processing and reduce regulatory paperwork and duplication. However, more needs to be done to reduce permitting delays and to ensure that permits contain only justifiable stipulations.

The GAO analyzed all the wetlands permits issued for such activity in Alaska during the period of February 1980 through September 1981 and found that 150 days was the average processing time for the 167 permits reviewed and only 40 of these permits were issued on time.

The Wetlands General Permit

In addition to granting individual wetlands permits, the Corps grants general and nationwide permits which cover generally minor and non-controversial projects having no significant environmental impact. In March 1979, the corps issued general permits for certain oil company construction activities on the North Slope. The permits covered the expansion of existing pads and the extension of existing roads on wet tundra. The average processing time for the letters of authorization for general permits was 63 days.

The Corps Testimony

Col. Neil Saling, testifying on behalf of the Corps, pointed out that the permit process provides an essential forum in which both the public and parties with an interest in the projects can discuss their concerns:

The heart of this decision making process is the public interest review. The public interest review stems from the provisions of the national Environmental Policy Act. The review, however, goes beyond traditional environmental factors and attempts to define first, whether the project purpose is in the public interest and, if so, how should it be constructed to maximize its worth to the public. The resultant balancing process requires public input as well as technical input from State and Federal agencies with particular expertise.

Saling agreed with the GAO report stating, “additional Arctic research is required and, in particular, further definition is needed of the roles of the various forms of tundra as wetlands and their relationship to the waters we are charged to protect.”

Industry and Administration Opposition

Roger Herrera, Manager of Operations for BP’s Sohio Alaska Petroleum Company, said at the hearing that since Prudhoe Bay was constructed, the Corps has become the dominant regulatory agency on the North Slope. “No significant improvement in the way these North Slope projects are planned or constructed has been introduced as a result of the Corps regulatory process,” he claimed. “Furthermore, the Corps regulations have shown themselves to be cumbersome, unwieldy and sometimes illogical, and they have resulted in delay, inappropriate stipulations and a huge increase in costs.” Herrera pointed out that in Alaska, the streamlined general permit process does not work because all the committing agencies must first concur. Otherwise, the applicant must go through the longer individual permit procedure.

Herrera then presented the outline of the new regulations proposed by Vice President Bush, acting through the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) which would greatly limit Corps control of the nation’s wetlands, especially where state and private lands are concerned. In these regulations supported by the oil industry, “wet tundra” would not be classified as wetlands, and the provisions of the Clean Water Act would apply only to navigable waters.

Don Glass of Shell Oil, speaking on behalf of the Alaska Oil and Gas Association, attacked the interpretation of the Clean Water Act that includes “vast reaches of disassociated wetlands even including wet tundra.” His testimony reiterated industry demands that land underlain with permafrost be excluded from the legislation, thereby eliminating Corps jurisdiction on the Slope:

Speaking first to the area problem, we believe the legislative history of section 404 offers little to suggest that Congress intended application of Section 404 controls so broadly as to include wet tundra areas as currently implemented in Alaska. Accordingly, we recommend Section 404 be amended to narrow the geographic scope of the program in Alaska to waters which traditionally have been considered “navigable” under the River and Harbor Act of 1899.

The testimony of Arco Alaska, presented by Senior Landman Tim Derigo, added more proposed changes in legislation: (1) The primary enforcement authority for wetlands be transferred to the states, and (2) The use of General Permits provisions become obligatory instead of optional.

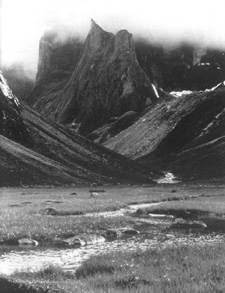

|

| Wet tundra in the Arctic: giving the Corps jurisdiction over 75 percent of the North Slope. |

Eben Hopson, Jr., speaking in behalf of the North Slope Borough, argued against any legislative alteration of the law and proposed, instead, that regulatory reforms take place on an administrative level. The Borough is “generally satisfied with the level of consultation and involvement that currently takes place,” he stated. “Section 404 Permit Review provides an excellent opportunity for the parties to discuss the scope of a project and its possible adverse effects on wetland areas and to reach agreement on construction or operating conditions which may be necessary to avoid adverse effects. It provides an effective and useful vehicle for the borough to present its concerns and has, on balance, served that purpose reasonably well.”

Ideally, Hopson admitted, “regulation of activities affecting North Slope wetlands should be a function of the state and local government. Because there remain many uncertainties regarding the ultimate environmental effects of development on wetlands, it is important to have available, for now, the resources of all governmental units, including the knowledge and experience of federal agencies and departments. Until many of the remaining issues have been resolved, such as ultimate classification of the lands of the North Slope, it is useful to have continued federal review.”

Hopson detailed the importance of wetlands to the people of the Arctic:

The wet tundra and other wetland areas along streams and rivers of the North Slope support extensive waterfowl, wildlife, and fish populations of the North Slope. The North Slope has an extensive nesting, breeding, and summer habitat for hundreds of migratory birds from the Lower 48 states. These wildlife populations are important to the continued subsistence lifestyle of the Native community…

Some wetland areas of the North Slope are more critical than others, and future development of the oil and gas resources of the North Slope is not necessarily inconsistent with protection of these habitats. but the areas are fragile and can be threatened by activities which are not well planned or are developed without appropriate protective measures. It should be pointed out, Senator, that once these wetland areas are destroyed, they cannot be replaced by any currently known re vegetation techniques.

…the protection of the North Slope’s wetland areas has national significance due to the migratory nature of the waterfowl, marine, and terrestrial mammals that rely on those wetlands. This is the case with other wetland areas of Alaska that support sport and commercial fishing and other natural resources which are of value not just to Alaska’s residents.

Hopson concluded by stating the need for a comprehensive master plan for development of the North Slope, something the NSB will have ready soon. “Such a plan would provide industry with advanced guidance on critical areas where special review will be required… The process for public involvement and state review of the North Slope Borough’s Coastal Management Program will make it a particularly useful and well-developed program that should be included within the federal administration of Section 404.”

Agency Support for Wetlands Regulations

While much of the motivation to centralize the permit processing at the national level and reduce the local review process comes from the Reagan administration, a good number of government agency spokespersons were present at the hearing to voice opposition to such a move. Chief among these was Ernst Mueller, Commissioner of the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation, who, though he saw the need for administrative reform, saw the need to retain the present classifications of wetlands:

We endorse wetland management plans which identify management appropriate to the resource values. There are areas of “wet-land,” areas underlain by permafrost or soils which do not drain. On the other hand, all wetlands underlain by permafrost should not be categorically dismissed as valueless or excluded from protection under the Clean Water Act. Resource values for wetlands in Alaska, including wet tundra, should be identified in the wetlands planning process and reflected in appropriate management strategies. Correspondingly, wetlands which lack public resource values can be developed in accordance with sound management practices.

Mueller stressed the need for completion of both state and local wetlands plans as the basis for “establishing boundaries of jurisdiction and important functions and values subject to regulation.”

|

Cliff Eames, counsel for National Wildlife Federation in Anchorage, stated:

The primary purpose of the Section 404 program is to restore and maintain the physical, biological and chemical integrity of the nation’s waters through regulating the disposal of dredged or fill material. Wetlands are an integral part of this nation’s waters and provide a number of essential functions that benefit society. Unfortunately, for years these wetland values have been misunderstood or overlooked, and as a result, the nation has lost more than 40 percent of the wetlands that once covered the lower 48 states. Let’s try not to repeat that mistake here.

Probably the most visible role wetlands play is the provision of essential habitat for fish and wildlife. Thirteen million ducks, geese, and swans migrate to Alaska in summertime and use wetlands as resting, breeding and nesting areas. These waterfowl create hunting opportunities not just in Alaska but nationwide as well. In 1980, 5.3 million hunters spent $658 million in pursuit of migratory waterfowl nationwide.

Wetlands also provide food, cover, spawning grounds, and nursery areas for salmon, trout, char, whitefish and other species of fish. The Kenai River system, for example, contributes as much as 35 percent of the total salmon population of Cook Inlet, and accounts for millions of dollars worth of salmon for the commercial fishery and many thousands of angler-days of recreational fishing. nationwide the wetland-dependent commercial fish harvest is valued at nearly $12 billion; in 1980 recreational fishermen spent roughly $13 billion of fishing activities directed towards wetland-associated species.

Many other species are also dependent on wetlands during a portion of their life cycle. These include moose, caribou, bear, bald eagles, beaver, song birds, and hundreds of other species, both game and non-game. In 1975 resident Alaskans spent nearly 13 million man-days enjoying wildlife-related recreational activities. Sportsmen alone spent almost $146 million in hunting and fishing-related expenditures. Alaskans, moreover, benefit from urban as well as rural wetlands, Potter Marsh being the most obvious example in Anchorage.

Congress, acting to protect these and other values, knew exactly what it was doing when it put the Corps in charge of “all waters of the United States” in 1972, according to Eames. In March 1975 the Federal District Court for the District of Columbia ruled that Congress intended the Corps to regulate dredge and fill activities in all waters subject to the commerce Clause. congress reaffirmed this decision in 1977 when it then rejected attempts to roll back the Corps’ jurisdiction.

Eames contended that, while the permit process could be made more efficient, nationwide permit processing does not take an unreasonable amount of time. There are “very good reasons why it should take longer on the average to process permits in Alaska,” Eames stated. “The vastness of the State and our sometimes less-than-benign weather increase the time it takes to perform the on-site reviews that can be essential prerequisites to fair and reasonable decisions. Some reviews aren’t possible except during the summer.”

Eames went on to give examples of now the permit-review process can even aid industry:

In 1981, an oil company applied for a permit to construct an oil and gas exploratory well pad in the Colville River that would destroy more than seven acres of wetlands. The area is extremely important for spawning and over wintering arctic char and whitefish. Whistling swans and polar bear also use the area. During the permit review process, it was recommended that the developer modify the project to use a new thin paid technique that reduces environmental damage and simplifies rehabilitation after the exploratory activities are complete. By adopting this recommendation, the applicant saved more than one million dollars in construction costs. The entire permit process took six months.

Eames concluded on a positive note that “Alaska’s program has matured into a balanced program of cooperation between federal, state, and local governments. Real progress is being made towards solving administrative problems that do exist.

David Cline, Alaska Regional Vice President for the National Audubon Society, talked about the rapidly diminishing wetlands habitat available for waterfowl nationally, and the urgent need to protect Alaskan wetlands.

|

| Canada geese at Potter’s Marsh near Anchorage: supporting a $25 billion-a-year industry. |

David Wigglesworth of the Northern Alaska Environmental Center in Fairbanks expressed concern about recent statements of Senator Murkowski concerning the relationship between the definition of wetlands and permafrost. On several occasions Murkowski questioned the inclusion of soils and vegetation underlain by permafrost in the definition of wetlands in Sec. 404.

“We feel it is clear that the North Slope wetlands meet the original intent of Congressional protection in that they are important national and international resources,” he said. One of the major indications of the wetlands designation is the use of wet tundra by waterfowl. Most of the birds on the Slope are water-related; some 75 migratory species use the area and 44 of them breed there, including the whistling swans, brant, white-fronted geese, pintail, eiders, oldsquaw, and plovers. Recent studies indicate that up to 5.4 million birds annually use the Coastal Plain. Ron Lautaret, representing the Sierra Club of Alaska, also supported the present definition of wetlands: “If the surface feature is wet, with plants rooted in saturated soil, regardless of whether or not it overlays an impermeable surface such as permafrost, it is a wetland. Congress intended to regulate such wetlands under Sec. 404. We are not aware of any scientific evidence contrary to the Corps’ definition of wetlands.

“Another important misconception which needs to be dispelled is that Sec. 404 prevents building or discharge in wetlands,” Lautaret added. “Nothing could be further from the truth. The Corps of Engineers records show that the overwhelming majority of permits (98.5%) requested in Alaska in 1981 were granted. If this trend continues, most of Alaska’s wetlands available for development will be used for construction rather than preservation.”

Wetlands Plans Applauded

Many of the participants had applauded the completion, in the Anchorage and Sitka Boroughs, of comprehensive wetland plans. Lautaret stated concerning the Anchorage plan:

The plan effectively demonstrates the value of region wide wetland planning. As a result of this plan, wetlands with high values for maintaining water quality, wildlife habitat, and urban open space will be protected. At the same time, certain lower-value wetlands will receive general permits for dredge and fill. (Incidentally, virtually all of the private wetlands in Anchorage were placed in a category which permits development.) With a regional wetland planning process in place, sound scientific research and data can be used to make decisions on general permits.

While the Clean Water Act authorizes the states to take over wetland management, none have chosen to do so, mainly because of the expense involved. If the Reagan administration has its way, however, there may be no other choice than for local and state governments to rapidly complete their own wetlands plans and shoulder the burden of protecting America’s wetland heritage.

| Below, the North Slope Borough’s Eben Hopson, Jr., at wetlands hearing in Anchorage: federal review of wetlands still useful. |  |

|

|