Kaktovik Subsistence

|

|

Kaktovik Subsistence: Land Use Values through Time in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Area by Michael J. Jacobson and Cynthia Wentworth U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Northern Alaska Ecological Services 101 12th Avenue, Fairbanks, Alaska 99701 1982. 142 pages with illustrations and maps.

This work is mainly a husband-and- wife effort. In 1977, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) set up a field station at Kaktovik and stationed an assistant refuge manager there for the first time. Michael “Jake” Jacobson was assigned to the post. One of his duties was to learn more about the subsistence way of life at Kaktovik. Jacobson set about learning from the local people, traveling and camping with them, and using their expertise by employing some of them in refuge projects.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Interior was beginning a new study of the historic, cultural, and Native dependence and livelihood values of the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (NPR-A). The North Slope Borough was contracted to provide Native livelihood information from all of its eight villages, including Kaktovik. Cynthia Wentworth, Mike Jacobson’s wife, was hired by the NSB to do the work in Kaktovik.

In May of 1977, the North Slope Borough’s Commission on History and Culture, under the direction of Flossie Hopson Anderson, prepared a “Traditional Land Use Inventory (TLUI)” of historic and cultural sites in the Beaufort Sea coastal area. This study, included in the Beaufort Sea Study by Jon Nielson published by the NSB in 1977, served as a baseline for compiling additional documentation on sites which have special significance for the people of Kaktovik.

While her husband was learning about the area’s wildlife resources, Wentworth expanded on the TLUI for the NSB NPR-A contract study. In May 1978, she began mapping subsistence resource use areas of selected Kaktovik residents as part of a new and larger subsistence mapping effort of the entire North Slope, directed by NSB contract employee Sverre Pedersen. Wentworth interviewed a sample of 13 Kaktovik hunters, representing about one-fourth of Kaktovik households, to determine the extent of the area used in hunting, fishing, trapping and gathering. Responses were combined to determine Kaktovik land use patterns.

Wentworth continued her work in Kaktovik later in the Borough’s Coastal Zone Management Program for which she compiled Kaktovik historic and subsistence information. Much of this work appeared in Qiniqtuagaksrat Utuqqanaat Inuuniagninisigun: The Traditional Land Use Inventory for the Mid-Beaufort Sea (NSB, 1980). This present work combines the research done by the couple during their years in Kaktovik, and was written while Wentworth was employed as an Economist with Northern Alaska Ecological Services, a Fish and Wildlife Service station in Fairbanks .

|

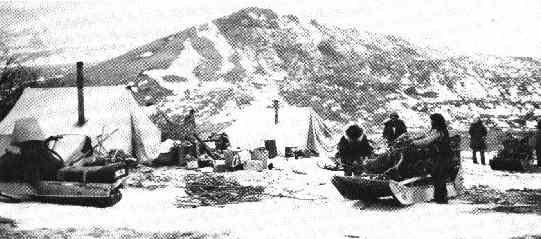

Left, crossing the foothills near the Hulahula River: land use patterns are a function of family tradition and personal experience. |

Susie Akootchook established the first trading post at Barter Island in 1923. |

|

Kaktovik, located on Barter Island, is the only village within the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Most of its 175 residents speak Inupiaq and are culturally and economically dependent on the refuge’s wildlife resources. Continuing petroleum development on the North Slope and its possible extension to the coastal plain of the ANWR have focused recent attention on the people of Kaktovik and their subsistence way of life. In order to minimize petroleum-related impacts and facilitate the best resource-allocation decisions, this report was prepared to represent the viewpoint and values of the people of Kaktovik regarding land use. The substance of the report is summarized in the following.

Barter Island, as the name suggests, has been an important trading center for centuries. Canadian Inuit people met here to trade with Barrow-area residents, sometimes while traveling to the trading center at Nigalik at the mouth of the Colville River. Inland people also came down from the mountains to trade, and even Indians from the south of the Brooks Range visited here occasionally.

A large prehistoric village once existed on the island. The first white explorers found 30 to 40 old house sites there. Even though it was not being used as a permanent village at the time, it remained a seasonal home for some of the nomadic ancestors of the present residents, who used the area in pursuit of caribou, sheep, sea mammals, fish and birds.

One legend says these prehistoric people, the Qanmaliurat, were driven east to the Canadian side by other Inupiat. Another account states that the disappearance of the village took place after the Qanmaliurat killed one couple’s only son. The story of the grieving couple’s fishing their son’s body out of the water with a seining net is reported to be the origin of the name of the place Qaaktugvik (Kaktovik), which means “seining place.”

Barter Island was an important stop for commercial whaling during the 1890’s and early 1900’s. In 1917, the whaler and trader Charles Brewer sent his associate, Tom Gordon from Barrow to Demarcation Point to establish a fur trading post there, one of a string of establishments along the Beaufort Coast. Andrew Akootchook, the brother of Agiak, Gordon’s wife, later moved to Barter Island and, in 1923, he helped Gordon set up a trading post there. The parents of Akootchook’s wife, Adam Alasuuraq and Eve Kignak and their son Ologak and his wife Annie Taiyugaaq moved from Barrow to Barter Island to be with their relatives and enjoy the good hunting there. The trading post provided a market for their furs and was the beginning of modern Kaktovik.

During the 1920’s and 1930’s, Barter Island people gathered at the trading post on holidays and other occasions, but most of the time they lived spread out along the coast, following the animals on which their economy depended. Many people became involved in reindeer herding, with three large herds at Camden Bay, Barter Island, and Demarcation Point, taking the deer to the foothills of the Brooks Range during the winter months. (Appendix 2 of the report gives a history of the reindeer era.) The late 1930’s saw both animal and economic declines in the area. The winter of 1935-36 was particularly severe and brought hard times to Kaktovik. In 1937, an unusual December rain fell on top of the snow and froze, making it impossible for the reindeer to get to their food supply and causing most to starve. Others were killed by wolves or taken for food and clothing.

To provide aid to the destitute community, a herd of 3,000 reindeer were driven from Barrow to Barter Island the winter of 1937-38. As the herd approached Barter Island, it turned back to Barrow, taking most of the remaining local deer with it. This dramatic event discouraged the people so much that they killed the few remaining reindeer and the reindeer industry came to an end. The price of fox fur also fell in the late 1930’s. Consequently, most of the Alaskan trading posts were closed by the early 1940’s. Hard times continued into the mid-1940’s for most Kaktovik people.

World War 11 had little effect on Kaktovik residents, but the post-war military build-up brought major changes. Barter Island was chosen as a radar site for the Distant Early Warning (DEW Line) system, which extended across the Alaskan and Canadian Arc- tic. This development provided jobs for area residents, and was the cause of three village relocations. In 1947, the Air Force built an airport runway and hangar facility on the site of the prehistoric village, necessitating the removal of several houses.

In 1951, the entire area around Kaktovik, some 4,500 acres, was made a military reserve and some people had to move again. In 1964, the village had to move a third time and received title to the present site, though not to the old cemetery nearby.

The availability of jobs from these projects caused a rapid increase in population , which jumped from 46 people in 1950 to 140 by 1953. The population re- remained stable until new developments in Kaktovik in the 1970’s beckoned some former residents to return there from Barrow.

The passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (1971), the founding of the village corporation and the North Slope Borough brought the greatest increase in job opportunities to Kaktovik. The great increase in Borough-funded jobs in the late 1970’s brought rapid change. In addition to new housing, a high school and a gymnasium with a small swimming pool, and a public safety building have been built. A fire hall and a new community center- medical clinic are soon to follow as a part of the NSB Capital Improvement Program. Villagers now have satellite TV and telephones in every home.

Before the military developments which began in the 1940’s, Barter Island people were much more nomadic and scattered. But even today, people have the desire and need to continue their land-related pursuits in spite of material changes. Present-day land-use patterns in Kaktovik are very much a family tradition and a personal experience. Families have the tendency to return to those places where parents lived or camped in their youth.

Those who have seasonal or intermittent jobs are free to be subsistence hunters the rest of the time, and those who are retired can hunt when they please. Modern advances are accompanied by the close economic relationship with the environment, the “subsistence economic system.”

Although the village corporation operates as a profit-making business, ideas of sharing money and other resources in the present take precedence over making money for the future. The economic system operates through strong kinship ties and alliances of the extended family, as every Inupiat in the village is related.

Sharing is prevalent not only with Native foods, but also with store-bought goods. Except for a very limited amount of arts and crafts production, Kaktovik people do not operate private businesses. One reason these inner socioeconomic values have remained intact through times of rapid change is that the surrounding landscape has not changed appreciably, allowing families to return to traditional hunting, fishing, and camping sites year after year, taking part in the same activities in familiar surroundings, as they have always done. Outings at these places provide them with maximum cultural privacy away from the rules of modern village life and the outside world. Thus, the outings afford the opportunity to strengthen family and kinship ties and the community values of sharing and helping each other. Although the Inupiat greatly enjoy these outings, they do not regard them as “outdoor recreation.” For them, subsistence is serious work as well as a favorite way to spend time, for work and pleasure are not separated for them as in western societies.

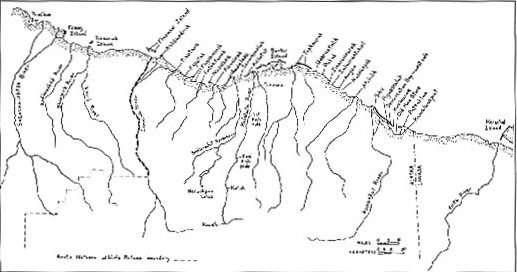

| Traditional Land use Inventory Sites, Arctic Notional Wildlife Refuge: in the Inupiat view, the land is a provider as well as a source of personal pleasure and cultural meaning. |  |

|

A principle of international economics states that world production will be most efficient if each country produces what it can produce best. Northwest Alaska Inupiat leader Tony Schuerch once stated, “I am sure the Eskimos are going to survive as a people, because survival is what we do best.” Traditional food-gathering activities not only supplement the wage economy, but also contribute to mental health by providing stability and cultural identity. Subsistence strengthens the family unit, provides meaningful work, and fulfills needs for personal self-reliance, self-esteem, and fulfillment. |

For all practical purposes in the Arctic, there are two seasons, summer and winter. During the ice-free months of summer, usually July through September , people travel by outboard-powered boats, and their activities are confined to the coast. But after freeze-up and during the snow season, from October to May, people can travel overland by snow machine.

Overall participation in subsistence activities is greatest during spring and summer months, as this is the time of long days, mild weather, and species abundance. The entire coast from Foggy Island to Demarcation Bay is used for summer subsistence activities.

The arrival of powered motorboats has allowed Kaktovik residents to conduct a fall hunt of the bowhead whale, which was not hunted in historic times until 1964. At the beginning of the fall migration, hunters may travel as far as 20 miles out to sea in search of the whales; later, in September, the whales pass closer to shore and may be taken within two miles of Barter Island.

After a rest from whaling, people work on their snow machines and start thinking of traveling south to the mountains. They usually wait for freeze-up and the closing of the narrow channel between Barter Island and the mainland (Tunuiguun). Along the Hulahula and Sadlerochit Rivers, there are favorite camping spots for ice fishing. During the fall, people primarily hunt caribou and sheep.

With the loss of daylight by mid-December, some people concentrate on trapping, which continues throughout the winter. During the winter, cross and red fox are taken, along with wolves and wolverines.

During the Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays, people who have been in the mountains return to the village for the traditional celebrations and the sharing of whale meat and maktak, caribou, sheep meat, and fish. There are also Eskimo games, dances, and snow machine races.

In January and February, people begin returning to the mountain camps, where the activities reach their peak in May, when squirrel, ptarmigan, and marmots are also taken.

Migratory waterfowl hunting begins along the coast in late May or early June, with birds appearing as soon as there is open water. Sometimes the last trips to the mountains are combined with the first trips for hunting waterfowl. During the approach to break-up, travel becomes more difficult and hunting takes place closer to Barter Island. People set up camps on the mainland close to the island or other locations where the birds are flying by. Late in June, subsistence activities slacken because of lack of snow for snow machines and the lack of open water for boat travel.

As soon as the ice goes out in July, there is a considerable increase in hunting as people begin to travel along the shore by boat. The legal season for caribou opens July 1 and they are taken when they are seen along the coast. July is also the best month for catching arctic char (iqalkpik), and people are seen setting their nets in Kaktovik Lagoon as soon as they can get their boats out. August and September are the best months for catching arctic cisco.

Chapter Seven of the report goes on to give much more detail of the taking of the individual species, giving good accounts of the hunts for the bowhead, caribou, sheep, fur-bearing species, waterfowl, and fish. Several appendices give the history of the reindeer-herding era and descriptions of the various traditional subsistence sites.

In a page of recommendations, the authors share their hopes that on site field investigations will be conducted on the subsistence sites of the Kaktovik people to determine whether or not the sites have archeological remains. They also recommend that such investigations be conducted using a multidisciplinary team consisting of an archeologist- ethnohistorian, a biologist, and former site residents–as were used in the investigations conducted by the NSB at Flaxman Island and Brownlow Point. Without these studies, they conclude, we cannot expect adequate consideration of Inupiat cultural values.

As a result of these recommendations, this multidisciplinary study was conducted by the North Slope Borough in summer 1982, led by David Libbey, an archeologist-ethnohistorian.

Masak Gordon butchers caribou meat at Kaktovik. |

Fox furs are hung out to dry. |

|||

|

||||