Arctic History – Land Use

NSB Publishes Study of

Early 19th Century Point Hope Land Use

The Traditional Eskimo Hunters

of Point Hope, Alaska: 1800-1875

by Ernest S. Burch, Jr.

Published by the North Slope Borough

1981

89 Pages – $10.00

|

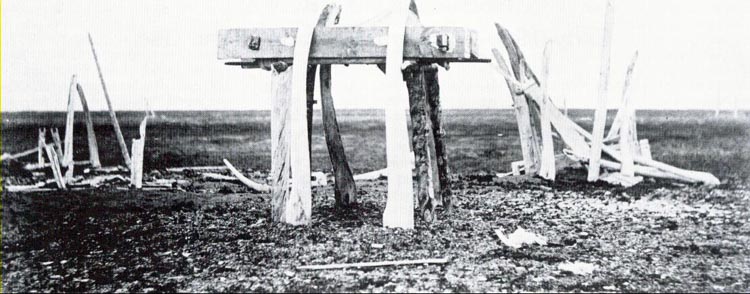

| Grave of an umialik at Tikirak, early 1880s. Point Hope had an enormous graveyard, a mile wide and five miles long. This grave appears to be very new and the flexed knees of the deceased can be seen behind the post on the right. The graveyard contained thousands of burials at the end of the 19th century. The early missionaries collected the remains from most of the traditional burials and placed them in a single mass Christian grave. Photo: The Kennedy Collection, The Whaling Museum, New Bedford, Mass. |

As the oldest continuously inhabited community in the Western Hemisphere, Point Hope is regarded among the Inupiat as a spiritual center which has remained faithful to the cultural traditions of the past. It is a powerful witness to the success of a society that has thrived in the Arctic for thousands of years.

When a cultural anthropologist as sensitive as Ernest Burch, Jr., comes to the task of defining the history and land use patterns of Point Hopers in the early 19th Century (just prior to contact with Westerners), a book such as his The Traditional Eskimo Hunters of Point Hope, Alaska: 1800-1875 is rewarding to all readers seeking to understand more of Inupiat culture.

Land Ownership Highlighted

While the purpose of the book is to give a comprehensive account of the ways in which the Point Hope People of the early nineteenth century used their land, three important issues emerge. The first is that the members of Point Hope Society were conscious of owning a clearly delimited territory. They referred to themselves as a nation, using the word nunatqiiglit, which meant “people who are related to one another through their common ownership of the land.” This fact was clearly understood by neighboring societies, whose own territories were similarly defined and controlled. This observation is in clear distinction with the traditional western view of Eskimos as nomads who freely roamed the country as they wished, doing whatever they wanted to do.

Related to territorial boundaries and the restrictions on land use was the protection of wildlife resources. Point Hopers were able to limit access to the harvest by keeping foreigners out altogether, and by the practice of the more powerful families among them of preempting settlement sites in the more productive districts.

A final point made in the book is that the experience of Point Hopers breaks down the view that there were two different types of Eskimos, the inland Nunamiut and the marine Tariumiut. This work supports the view that Eskimo economies were neither inland or marine but Arctic adapted, and each society depended on a combination of marine and terrestrial species. Nowhere is this more evident than among Point Hopers, who took advantage of being in one of the best shore whaling locations in the world, but also availed themselves of the other resources the country offered. The following is a synopsis of the book.

Chapter I -The Land

Point Hope is an Eskimo village located near the end of a point which projects several miles into the Chukchi Sea from the coast of Northwest Alaska. The point resembles a huge finger pointing at Asia, and is thus referred to by the Natives as Tikiraq, meaning “index finger.” The people owning and living on the land in and around Point Hope are called Tikiarmiut. The Point Hope Region occupied by the Tikiarmiut during the Traditional Period under discussion (1800-1875) included some 4300 square miles, reaching from Kemegrak Hills on the south to Lisburne Hills and Cape Beaufort on the north. The boundaries inland included the drainages of the Kukpuk and Pikmigiam Rivers. The area geographically is part of the Arctic Foothills Province laying to the west of the Brooks Range.

The winter temperatures are normally above -30 degrees F., but the strong northerly winds from the Arctic Slope flowing around the western edge of the Brooks Range makes the Point Hope area one of the most uncomfortable in the world. Annual average precipitation is between 8 and 12 inches.

The area is characterized by Arctic tundra flora including dwarf shrubs and trees, grasses, sedges, lichens, moss, berries, herbs, and flowers. The Region is seasonal home to some 120 species of birds, 25 species of terrestrial animals, 15 species of marine mammals, 55 species of fish. Some 70 of the major species are known to have been important subsistence resources to the traditional Point Hope People. These include the bowhead whale, the walrus, the beluga, 3 species of seal, the caribou, 8 species of fur-bearing animals, the polar and grizzly bear, 14 species of fish, 25 species of birds, and 12 species of invertebrates.

The Tikiarmiut were blessed by the fact that the annual cycles of the major prey species were not synchronous with one another. The general abundance of game, the ability to preserve much of their harvest for long periods, and the skillful coordination of their movements with those of the major prey species enabled them to achieve one of the largest human populations of any Native Arctic people in the world.

Chapter II – The People

|

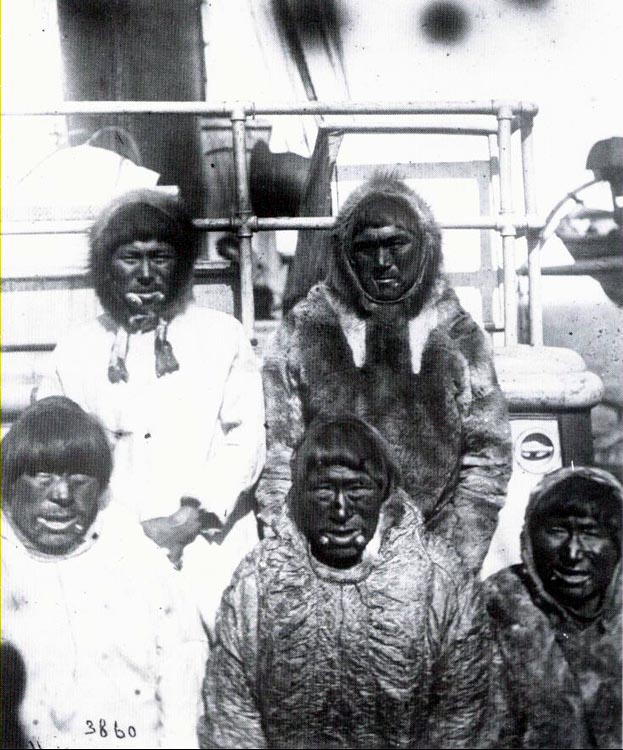

| Point Hope men aboard the “Corwin,” 1881. All are wearing labrets, the typical ornament of adult males among the Northwest Alaskan Eskimos. The man on the right, back row, is wearing a caribou skin parka, with the fur side out. The man on the right, front row, appear to be wearing a caribou-skin parka with the fur side in. The one in the middle front row has a waterproof parka, probably made from the intestines of the bearded seal. The other two are wearing white drilling, obtained from traders, over their skin parkas. The man in the back row, left, is the legendary Atanauzaq. The others are not identified. Photo: E.W. Nelson Collection, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution. |

Scientists have reported that the first people arrived in Point Hope thousands of years ago. But the oldest evidence of human occupation by the ancestors of the Tikiarmiut dates from about 600 B.C. The Tikiarmiut appear at the beginning of the 19th century as a large and powerful group of people speaking the North Slope dialect of Inupiaq languages.

The land owned by the Tikiarmiut was defined by well-known boundaries. Foreigners crossed these boundaries at considerable risk unless they came under certain long established conventions governing neighboring nations. The Tikiarmiut were by no means isolated. Their land was joined by that of the Kivalinarmiut (Kivalina Society) to the south and the Silalinarmiut (Northwest Coast Society) to the north and the Utuqqarmiut (Utukok River Society) to the east.

The population of the Tikiarmiut around 1800 was about 1342. Because Point Hope was the largest and most powerful society in Northwest Alaska, it was a nation surrounded by enemies bearing deep grudges which they attempted to redress by force of arms. The resulting battles caused a significant decline in the Point Hope population during the first half of the 19th century. The first battle was fought against neighbors from the east and resulted in the deaths of at least 200 Tikiarmiut, a major disaster for the society,

A second event happened when Indians living on the upper Noatak River attacked the village of Nuvuraluaq, a suburb of Point Hope, trapping the inhabitants in their houses and killing the entire population of more than 50 people. A third event took place about 1838 when people of Kotzebue Society (Qikiqtarzugmiut) attacked another settlement near Cape Lisburne, killing some 70 Tikiarmiut.

The Tikiarmiut were by no means passive about all this. They had successfully repelled many raids on their main village of Tikiraq and were very active in mounting attacks of their own from the Colville River to the North, to the upper Noatak River to the east to Kotzebue Sound on the south.

The Late Traditional Period:

1849-1875

With the arrival of the American whaling ships in 1849, the citizens of Point Hope began to experience profound changes. The whalers and their suppliers, at first wary of the inhabitants of Tikiraq, soon began to visit them frequently.

Around 1865 an epidemic of measles broke out in the Region and ravaged whole villages. While this epidemic was possibly the worst in the history of the Tikiarmiut, it was only the first of a long series.

At the same time the people were coping with the ravages of newly-introduced disease, the newcomers were depleting needed subsistence resources. By 1854, it was reported that whales had become very scarce and they continued to decline in numbers over the next several decades. By the 1860’s the whale stocks were so depleted that the whalers turned their attention to walrus. Within 15 years, the walrus population was also decimated. During the 1870’s, other scourges were introduced by visiting whaling ships and traders in the form of alcohol, tuberculosis, and venereal disease.

The Period of Instability: 1875-1900

At a time when the society of the Tikiarmiut appeared to be crumbling, two factors were at work which seemed to shore it up. The first was the influence of Atanauzaq, a powerful, intelligent and generous Tikiraq leader who had developed some remarkable entrepreneurial skills in trading with the American traders and whalers. Through a combination of luck, skill, and a facility with English, he became established as the middleman between the entire Point Hope population and the outsiders.

While during his early years, the legendary Atanauzaq was a positive factor in the life of Point Hope, he later became corrupted by his own power. He began killing people, taking other men’s wives, and acting capriciously. Many families emigrated from Point Hope to escape his influence, and those who stayed plotted his demise. He was finally assassinated February 14, 1889.

A second stabilizing influence was the work of the U.S. Revenue Marine Service, the forerunner of the Coast Guard. During the 1870’s Revenue Marine cruises were begun to enforce the law against selling alcohol to Natives. It seems these were successful in at least inhibiting the American whalers from indulging in their worst excesses among the Tikiarmiut.

In the winter 1885-1886, one of the worst disasters befell the people of Point Hope. The whale, walrus, and caribou populations had already been depleted, and that winter, the other species collapsed as well. Dozens of people starved to death.

In 1887, another development began which had lasting impact on Point Hope, and that was the establishment of’ shore-based whaling. The whalers brought people from the Seward Peninsula to work the stations. Many of’ these people left the area to settle in Kivalina when the whaling season was over. This annual migration to and from Point Hope Region was later increased by workers coming from the Noatak and Kobuk River areas, which were highly impacted by the scarcity of caribou. The regular movement of outsiders to Point Hope for spring whaling has been typical of the 20th century and dates from this time.

The Period of Readjustment:

1910-1980

Alter the collapse of the baleen market, the area was supported by the new demands for furs which were abundant in the Point Hope Region, and the establishment of a domesticated reindeer industry in the area. Also important was the increasing presence of both the church and a variety of U.S. Government agencies. A basis for integration into the larger U .S. society was established.

“They referred to themselves as a nation, using the word nunatqtiglit, which meant ‘people who are related to one another through their common ownership of the land.'”

Both the fur and the reindeer industry collapsed with the Great Depression of the 1930’s. This caused the retreat of the trappers and herders back to Point Hope to exploit the advantages of village life. Although the people were now concentrated in the village instead of remote settlements, greatly improved methods of hunting and travel gave the Tikiarmiut a new ability to travel far and exploit their traditional hunting grounds.

Chapter III: Land Use — The Production of Raw Materials

The Traditional Tikiarmiut harvested the raw materials of the land by hunting the wildlife available to them where they lived. From animals they obtained virtually all of their food, clothing, tools, utensils, weapons, and most of their other physical possessions.

Their chief source of food was the bowhead whale, which passed close by Point Hope twice a year, in the spring and fall. The primary whaling season was in April and May, and the major whaling location was located just south of Tikiraq, where as many as 20 whaling crews lined up on the edge of the landfast ice waiting for the whales.

Each crew, consisting of a helmsman, a harpooner, and six paddlers would mount a 24-hour watch for surfacing whales. When one appeared, the boat would be launched in pursuit, the first task was to attach a set of sealskin drag floats to the whale by means of a harpoon. The next objective was to kill the whale by means of lances and magical songs. Several other crews would come to assist and would share in the harvest. Once the whale was killed, the task became one of towing it to the edge of the ice, butchering it, and getting it ashore.

Whale hunts also took place in the fall, and a spring hunt took place at Point Lisburne. But both these practices produced fewer whales and were finally terminated when the whales were depleted in the 1850’s. Beluga whales were also hunted at Point Hope, appearing first with the first runs of bowhead in April and then another run in July, two months after the first group had passed, For unknown reasons, the supply of beluga, which were never exploited by the American whalers, has diminished considerably.

Walrus also were known to visit Point Hope twice a year, beginning with the opening of the shore leads throughout June and again in September, when the animals migrated south. Swimming walruses were hunted much in the same manner as hunting whales and were harpooned. Walruses on shore were killed with lances or bludgeoned with clubs.

The three types of seals available at Point Hope were hunted by a variety of techniques, depending on the species and the season. In the fall, they were hunted close to shore in kayaks. In winter, they were hunted at the breathing holes. In the sunny days of spring when the seals basked on the ice, they were often stalked and harpooned on the ice.

Caribou was as important to the Tikiarmiut as the marine mammals because of their dependence on caribou for hides, sinew, antlers, and bones used for making of most of their clothing, tents, blankets, tools, and weapons. Caribou meat, fat, marrow, and viscera also formed an important part of their diet. The Traditional Tikiarmiut harvested the caribou using many different techniques.

One of the best techniques was to drive a band of caribou up between two converging lines of ‘scarecrows” (inuksut) into an enclosure made of bundled willows and brush placed upright and covered with earth and moss. Up to 200 caribou at a time could be trapped this way. Snares were employed at other times, along with pitfalls. Caribou were often shot with bow-and-arrow and sometimes speared while swimming.

Available fish included cod, Dolly Varden, whitefish, and three species of salmon. These were taken in a variety of methods including seine and gill nets, traps, spearing, and hooking.

Point Hopers were accustomed to take about 30 species of fowl, which fell into four categories: sea-cliff birds, ducks and geese, gulls and terns, and terrestrial birds. Murres make up most of the sea-cliff birds and arrive in the Region in early May. They were hunted with bolas as they crossed the tip of the Point at low altitudes. After they began nesting, their eggs were gathered on the cliffs. Ducks and geese were hunted during May and June primarily using the bola.

The eggs of gulls and terns were considered a delicacy. Terns were rarely killed, but gulls were taken by bow-and-arrow or snared at the nest. During the summer, the sandhill crane was taken. In the fall, the snowy owl was available. Ptarmigan are taken throughout the year.

Vegetable products included berries taken in season, and willows, dwarf birch, moss, and grasses ere harvested for house frames, fuel, insulation, wicks, and tinder. Mineral products utilized from the land included slate for knives and spear points, flint for arrowheads, scrapers, and starting tires, sand for grinding, and clay for making pots. Hematite was used for dyeing skins. Pyrite (ignik) was used for starting fires.

Chapter IV: Land Use -Social Dimension

At any one time, the Tikiarmiut occupied only the tiniest portion of the region they owned. This chapter explains the complex factors which determined where they were all to be found at any one time. Generally, the suitability of any place for human occupation depended on the availability of animal food resources, but that was not the only consideration. There were also dangerous creatures and ghosts whose presence pre-empted usage of certain places as settlement sites.

The fact that 19th century hunting took place on foot meant that an array of settlements had to be placed throughout the area, each of which could provide “very easy access” (around five miles) to important hunting areas. Except during whaling season, the Tikiarmiut tended to disperse throughout the Region at a number of these locales.

Generally, there were four types of settlements: summer settlements, interior settlements, out lying coastal settlements, and the single settlement of Tikiraq at Point Hope.

During the summer, Tikiraq was virtually abandoned as the people lived in permanent settlements near the bird cliffs at Capes Thompson and Lisburne, or dwelled in tents at other spots good for fishing and beluga hunting. Travel was done mainly in the skin boat umiaks which carried the sealskin or caribou skin tents and other baggage.

Toward the end of August, the dispersed summer groups began to move to their fall locations. This could be either on the coast, but several were at the interior settlements on the Kukpuk River where fish and caribou would be available. As many as 200 people would be living along the lower Kukpuk in some 15 different settlements, with houses covered with sod, caribou skins, or moss. As winter came on, several groups would move even further inland to take advantage of the caribou hunt. There they would live in the same skin or moss covered houses or snow houses.

The outlying coastal settlements, along the northern coast between Capes Lisburne and Beaufort, tended to be more stable than the interior settlements, with habitants leaving only for the spring whaling season in Tikiraq. The population in these settlements harvested caribou and seal.

Tikiraq, the main settlement of Point Hope People, was evidently not very impressive to the first Europeans who visited there, but was actually one of the largest settlements in the Eskimo-spreading world. Tikiraq is distinguished from the other settlements not only by its size (about 600 lived there at the beginning of the 19th century), but by the fact that it was occupied by families not related by blood. All the other settlements were occupied by extended families and those related to one another. It was so large, in fact, that many of the adults did not know each other’s names.

The society of the Tikiarmiut was divided into what others today would call large extended families. The Native term for such a unit was amilraq or amilraqtuyaat. These extended families would be as large as 70 – 75 people and would dwell in a cluster of sod houses. All of the settlements except Tikiraq would be occupied by the members of just one of these families. Tikiraq itself is best understood as being a large settlement made up of’ a number of these family-clustered houses located unusually close together.

Over the years, the different families at Tikiraq evolved various ways for the different families to facilitate social cooperation. One was the qalgi, a place for group activities – dancing, feasting, ceremonies, and community work. “Qalgi” could be any assigned place or a building. The term was also used to designate the organization that used that place, in the same way as the English use the term ”lodge” for both the place and the organization. The social organization of the qalgi became quite formal over time. The building itself was originally built by a very large and powerful family which first extended membership to related family groups. Each qalgi tended to he dominated by one or more large families. Six qalgis were interspersed among the houses of’ Tikiraq in the early 19th century.

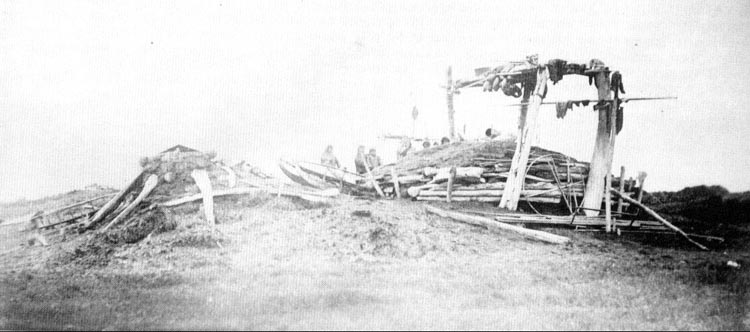

The structure of the family-clustered houses was impressive. They were often connected by passageways and included caches, storage racks, cold storage, and other support features nearby. Each cluster in Tikiraq had its own name.

An impressive feature of Tikiraq was the enormous graveyard that extended northeast from the community. It was five miles long and a mile wide and is said to have contained several thousand corpses at the end of the 19th century. Other areas of the community included playing fields and an archery range where men and boys could practice shooting.

A final feature included a defense zone of spikes made of baleen and caribou bones that were strategically placed in three parallel rows. The spikes protruded from the ground just a few inches. The battle strategy was to drive attacking forces back onto the spikes where their feet would be impaled and their mobility impaired.

Chapter V: Land Use – The Temporal Dimension

|

| Winter house, along with storage and drying racks, Tikiraq, early 1880s. Living quarters are under the racks. The entrance passage is on the left. Photo: Kennedy Collection, The Whaling Museum, New Bedford, Mass. |

The movements of the People of Point Hope were related to the movements of the migratory food species on which they depended. A lot of timing was involved, not only to be at the right place when the species arrived, but to have all the necessary gear and supplies ready for that particular hunt.

Much depended on the regularity of the animals. While minor variations in their schedules happened every year, major variations were matters of great concern. Over the generations people had developed sonic ability to predict many of these changes a month or two in advance. They could then alter their plans and make adjustments. Wrong judgments could result in hunger and famine.

It was in the spring of the year that people began directing their subsistence activities towards the systematic accumulation of supplies for the following year. People gathered at two locations, Tikiraq and Ulivak, near Cape Lisburne for the beginning of the spring whale hunt.

At Tikiraq, the first task was the clearing of an ice road, necessary for dragging the sleds to the water’s edge. This task required everyone’s cooperation. Once the road was built, the crews spread out along the shore lead as they wished.

By mid-April, it is light enough to see all night at Point Hope. So the bowhead were hunted at all hours, whenever they appeared. When no bowheads appeared, attention turned to belugas. When there were no whales at all, men and boys hunted with bolas the thousands of waterfowl that flew along the shore at that time of year.

Most of the meat and blubber of the whales, beluga, or seals that were caught was stored in cold storage. These were ice cellars dug 15 feet or so into the permafrost. The deeper ones had two floors. Each family usually had one or more of these ice cellars, which were an important factor in the efficient maintenance of a large population of people. At the end of whaling, the crews returned to the settlement and preparations took place for the whaling feast, nalukataq, which took place a couple days later and lasted for a week.

During the spring-summer transition, a period between the whaling feast and the final disappearance of the sea ice, the primary land use activity was the hunting of bearded seal and walrus, ringed seal, and waterfowl – given that order of priority. A significant number of families moved out to their summer camps during that period.

Bearded seals were sought mainly for the size, workability, and toughness of their skins. They weighed several hundred pounds each and supplied much food to be stored in the ice cellars. Some was dried and stored in pokes of seal oil. Some was eaten after aging a few days on the sand.

The beginning of summer opened the sea to the Tikiarmiut for travel and presented them with a variety of options as to where they could go and how they were to spend their time. The options were (1) land-oriented hunting and gathering, (2) coast-oriented hunting and gathering, and (3) trading. Though a group might have done one more than another, often a variety of goals were pursued at any one time. Tikiraq was relatively abandoned during summer, and many groups left the Point Hope Region altogether, indicating that the subsistence area was larger than the area of political control. This situation was made possible by the general inter-societal truce during the summer months.

Several went hunting caribou, for example, in inland territory actually owned by the neighboring Utukok River Society, but occupied by them at other times of the year. Summer caribou hunting was important for clothing. The skins were prime condition for clothing only at that time of year. Entire family groups would walk slowly inland up river drainages with the help of pack dogs, carrying lightweight camping gear, hunting snares, tents and food in the form of whale blubber and seal oil. When a caribou was taken, it would be prepared and dried on the spot and stored in a cache. Some families hunted marmot and ground squirrels as well.

Those who chose to summer on the coast continued seal hunting and began the egg gathering. When caribou occasionally came to the coast, they were pursued and hunted also. Beluga were still available and the coast was visited by migrations of salmon and charr which were taken by set nets anchored perpendicular to the shore. People on the shore gathered berries and greens, and hunted waterfowl and squirrels.

The third major activity was the trade fair held at Sheshalik on Kotzebue Sound. From 50 to 100 would travel in boats from Point Hope to meet with people from the entire Kotzebue Sound region, and even a few boatloads from Siberia. They traded oil, seal and whale meat, muktuk, seal and walrus skins, and rope for Russian tobacco, jade, pottery, Siberian reindeer skins, beads, caribou skins, and furs.

Towards the end of August, people began moving back to Tikiraq. Even those who were to winter elsewhere would make a point to visit Tikiraq during the fall to retrieve stored food, to visit relatives, and to enjoy the festivities celebrating an abundant summer. Then many would take off for the fall hunting camps along the coast all the way to Cape Beaufort and up the Kukpuk River. On the north coast, walrus and mountain sheep would be taken. In the south, people would seine for fish until the sea froze. In the inland, salmon, charr, and grayling were taken, and caribou hunted.

The beginning of winter brought the harvest of ringed seals. From this time forward, the harvest of ringed seals became the primary subsistence activity of every able-bodied man. The Point Hope hunters gradually extended their sealing operations at a gradual pace as the ice conditions allowed. Both the breathing hole technique and nets set under the ice were used. Polar bear were also hunted as they appeared.

January found older people and children jigging for cod through holes cut in the ice. A month later the same people were found catching crabs using similar techniques. In the inland, food supply was less stable and the people would be more likely to move following the herds. As a result, Point Hope people were apt to be more dispersed in February than October. But by March, they all began the trip back to Tikiraq to prepare for whaling season.

For many that meant a long and cold trip. But as the author writes: But the compulsion to hunt the bowhead was ingrained in the Point Hoper’s psyche as well as in his stomach. Nothing but death itself would keep a hunter from joining his crew. As a result, late March would find the entire Point Hope population again situated in just two places, bringing a close to the cycle which had begun the year before.”